Busby Berkeley’s Thematic Vision: Spectacle, Storytelling & Social Dynamics in the Early Hollywood Musicals

Berkeley's vision

Busby Berkeley’s kaleidoscopic spectacles weren’t just dazzling dance routines — they were visual stories layered with fantasy, power plays and cultural commentary. In this post, we explore how Berkeley balanced story and spectacle, his use of surrealism and abstraction and the complex gender and racial dynamics embedded in his most iconic sequences.

Further Reading

Narrative and Number in Busby Berkeley’s Footlight Parade by Natasha Anderson

Academic article which dissects how Berkeley transforms plot into spectacle.

Read it here

Buzz: The Life and Art of Busby Berkeley by Jeffrey Spivak

A rich and engaging biography exploring Berkeley’s life, innovations, and contradictions.

Buy it here

Showstoppers: Busby Berkeley and the Tradition of Spectacle by Martin Rubin

A llook at Berkeley’s visual style and its place in musical and cinematic history.

Buy it here

Race and Representation: A Problematic Legacy

Revisiting Busby Berkeley’s golden‑age musicals can feel like stepping into a glittering dream — until a jolt of 1930s Hollywood reality shatters the illusion. Amid the kaleidoscopic chorus lines and swirling camera work, Berkeley’s films carry the fingerprints of their era’s racial blind spots, from minstrel caricatures to exoticist fantasy.

Goin’ to Heaven on a Mule from Wonder Bar (1934) is now widely condemned as one of Berkeley’s most racially offensive musical numbers. Its grotesque racist stereotypes are a reminder of how Hollywood’s golden‑age spectacle could coexist with deep racial insensitivity.

Across Berkeley's output, when an ocasional non-white performer appears, they are pushed to the periphery, reduced to caricature or comic relief, denied entry to Berkeley's gleaming worlds.

Berkeley’s genius for spectacle is undimmed, but these sequences remind us that Hollywood’s golden glow was built on selective vision. To marvel at the craft today is also to reckon with the prejudice woven into its frame.

Gender, Eroticism and Visual Power

The Female Body as Spectacle

Berkeley’s work is often read as both celebratory and objectifying. His choreography reduced chorines to stylised components of a grand visual machine. Dancers became coins, violins, fountains, or “living architecture” — stripping away identity in service of form. Sequences played with voyeurism and containment — “no-men-allowed” zones of feminine spectacle, framed for the gaze.

Power, Precision and Control

Berkeley’s military background and perfectionism led to a directing style sometimes described as “fascist” — total control over rhythm, repetition and symmetry. Warner Bros., with its ensemble casts and looser narrative structure, gave Berkeley the power to make the musical number the main event. At MGM, the dominance of stars like Judy Garland and Mickey Rooney shifted focus from spectacle to character, making Berkeley’s abstract tendencies more restrained.

Eroticism and Ambiguity

Berkeley’s pre-Code numbers often teased eroticism — silver body paint, barely-there costumes and suggestive choreography. Post-Code, he channeled this into symbolic fantasy. Million Dollar Mermaid (1952) showcases Esther Williams in aquatic pageants that emphasise the athletic, near-mythic power of the female body — a different but still stylised kind of eroticism.

Fantasy, Abstraction, and Surrealism

A Dance Director's Dreamworld

Berkeley’s imagination defied realism. His sequences created fluid, disorienting dreamscapes — like pianos moving by themselvves or a series of giant rcking chairs being blown up.

Gigantism and Miniatures: Props and scale constantly warped perception — from colossal coins (“We’re in the Money”) to mountains of fruit (“The Lady in the Tutti-Frutti Hat”).

Surreal Transitions: Ruby Keeler’s floating heads in Dames or the aquatic delirium of “By a Waterfall” created moments of deliberate, dreamlike unreality.

Kaleidoscopic Abstraction: Geometric formations of dancers turned women’s bodies into pulsing, dehumanised patterns — art deco shapes, glowing harps, human mandalas.

The Camera as Choreographer: The real “dancer” in Berkeley’s numbers was the camera — gliding, swooping, flipping perspective. It offered what critic David Thomson called “arbitrary and gratuitous design” — the joy of visual excess untethered from logic.

Spectacle as Detached Fantasy

Despite these moments of thematic alignment, Berkeley himself often dismissed plot as secondary — he is said to have “never cared much about the story.” At Warner Bros., the “backstage musical” format gave him license to create hermetically sealed dreamscapes, untouched by narrative logic.

Some numbers ran well past conventional limits — “Lullaby of Broadway” (1935) clocks in at nearly 14 minutes — fully embracing spectacle for spectacle’s sake.

At MGM, his expressive freedom was curtailed by the demands of star vehicles. His sequences became more “integrated” but less formally daring.

In later films like The Gang’s All Here (1943), story all but evaporates under a barrage of surreal images — bananas, polka dots and Carmen Miranda’s headdress — taking fantasy to its visual extreme.

How Spectacle Served Story — or Vice Versa

Narrative-Driven Spectacle

During his Warner Bros. peak — 42nd Street, Gold Diggers of 1933, Footlight Parade — Berkeley’s choreography often did more than entertain: it amplified theme and story.

42nd Street ends with a meta-musical sequence that spirals into a storytelling free-for-all: gangsters, guns, showgirls and street scenes collide in a frantic finale.

In Gold Diggers of 1933, “Pettin’ in the Park” sets a cheeky tone of pre-Code mischief, while “Remember My Forgotten Man” confronts Depression-era suffering head-on — a rare instance of overt political messaging in a musical number.

“Shanghai Lil” in Footlight Parade blends racialised fantasy and patriotic pageantry in a number that’s simultaneously celebratory and troubling.

Watch

Still live at time of posting — these clips highlight the intersection of spectacle, story and social complexity in Berkeley’s work.

“Remembr My Forgotten Man” – Gold Diggers of 1933

A searing, Depression-era number blending stylised choreography with raw political expression.

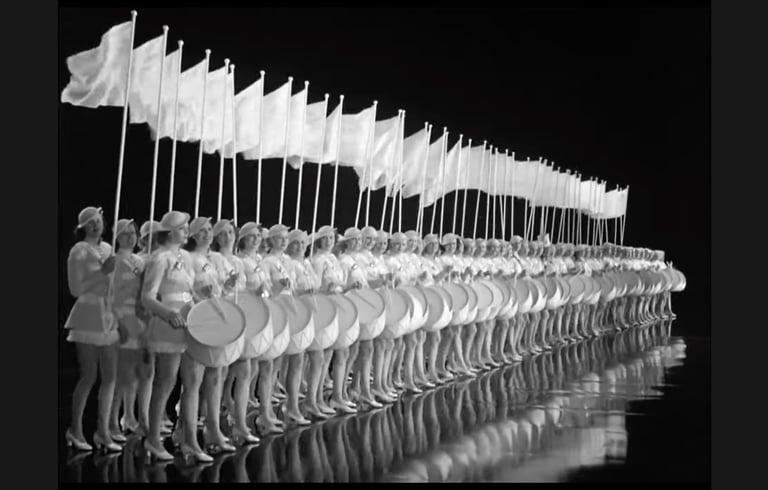

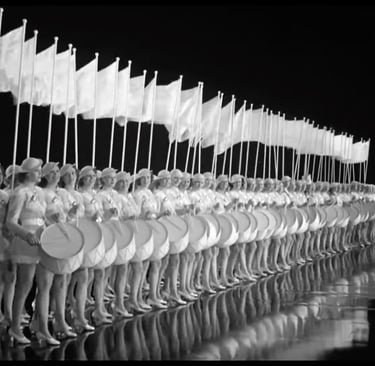

“All’s Fair in Love and War” – Gold Diggers of 1937

The battle‑of‑the‑sexes staged as a full‑blown military revue. Expect chorus girls in gleaming white uniforms marching, tap dancing on oversized rocking chairs, explosions and 1930s gender politics.