Busby Berkeley and the Warner Bros. Musicals: Reinventing the Early 1930s Stage-to-Screen Spectacle

Berkeley's early film career

Busby Berkeley’s Warner Bros. Breakthrough: Escapism, Spectacle, and Survival

Intro

When Busby Berkeley arrived in Hollywood in the early 1930s, the movie musical was in trouble. The novelty of “all‑singing, all‑dancing” talkies had worn off, the Great Depression had decimated box office numbers and studios were panicking. Then came Berkeley—a former Broadway dance director with no formal training—who looked at the camera and thought, “What if this thing could dance too?”

At Warner Bros., he hellped fashion a new kind of musical: part gritty backstage drama, part surreal visual fantasy. His kaleidoscopic overhead shots, human fountains and hypnotic formations didn’t just dazzle Depression‑era audiences—they helped save a struggling studio and defined the “Berkeleyesque” style for generations to come.

Further Reading

Hollywood Be Thy Name: The Warner Bros. Story by Cass Warner Sperling & Cork Millner, with Jack Warner Jr.

A family and studio history, revealing the backdrop against which Berkeley’s musicals saved Warner Bros. from financial ruin.

Buy it here

42nd Street (BFI Film Classics) by J. Hoberman

A pocket‑sized commentary that dissects 42nd Street with critical clarity.

Buy it here

Who’s in the Money?: The Great Depression Musicals and Hollywood’s New Deal by Harvey G. Cohen

A political history of 42nd Street, Footlight Parade and Gold Diggers of 1933 which reveals how studio moguls and musical numbers became unexpected players in America’s economic drama.

Buy it here

Watch

“Pettin’ in the Park” – Gold Diggers of 1933

A playful, pre‑Code spectacle that mixes humour and flirtation, complete with gleaming metal costumes that need a can‑opener to remove.”

Escapism Meets the Great Depression

Berkeley’s Warner Bros. musicals worked because they were both of the Depression and a dazzling escape from it. Audiences saw their own economic struggles reflected in the backstage plots, then were lifted into surreal fantasy by his dreamlike camera choreography.

His genius was in the juxtaposition: bleak streets outside, kaleidoscopic bliss inside. For two hours, moviegoers were reminded that beauty and hope could still exist, even if only on a 30‑foot screen.

Key Films of the Warner Bros. Era

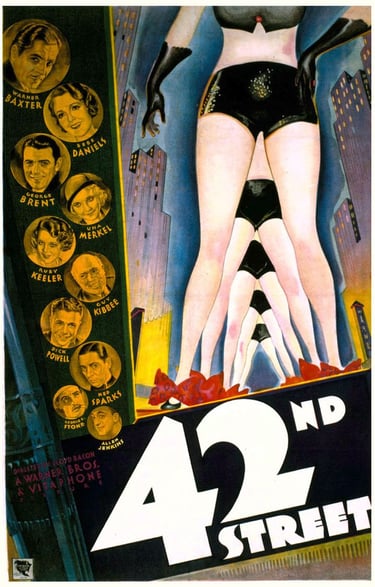

42nd Street (1933)

The film that redefined the musical. While the narrative stayed mostly backstage, the numbers burst free of the stage entirely. “Young and Healthy” showcased his first great swirl of overhead formations and the title number gave audiences a brassy, urban showstopper that felt ripped from Depression‑era streets.

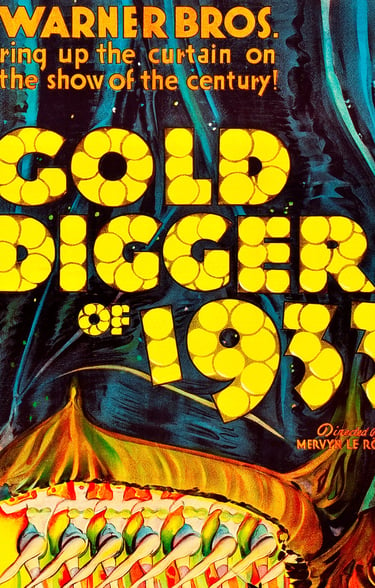

Gold Diggers of 1933

Berkeley’s imagination hit full throttle here. Giant coins, cheeky eroticism and social commentary blended into visual symphonies. “We’re in the Money” radiated optimism, while “Remember My Forgotten Man” offered a haunting portrait of economic despair—perhaps the most political musical number of the decade.

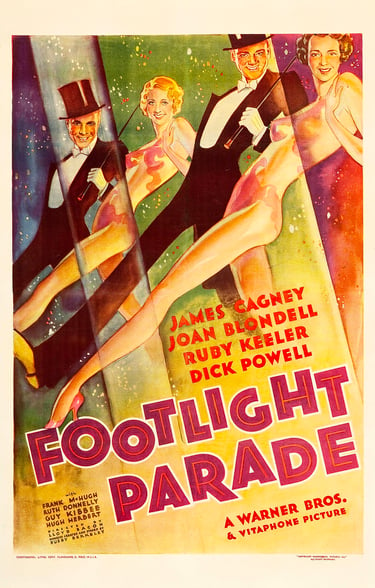

Footlight Parade (1933)

If 42nd Street was the breakthrough, this was the coronation. “By a Waterfall” unleashed an aquatic ballet of 100 synchronised swimmers, captured in dizzying crane shots, while “Shanghai Lil” turned patriotism into a kaleidoscopic carniva.

The Warner Bros. Rescue Mission

By 1932, Warner Bros. was on the brink. Executives Mervyn LeRoy and Darryl F. Zanuck brought in Berkeley to inject life into their faltering musicals. The formula he developed in this classic Warner period (1933–1934) was simple but revolutionary:

Gritty Urban Realism by Day: Struggling chorus girls, desperate producers, and Depression‑era hardships.

Otherworldly Escapism by Night: Human kaleidoscopes, geometric dreamscapes, and delirious spectacle that defied gravity—and narrative logic.

Audiences were hooked. They bought tickets not for the stars (Warner Bros. had few at the time), but for Berkeley’s numbers.

From Broadway to Hollywood: Reinventing the Musical

Berkeley’s journey to Hollywood was as unconventional as his choreography. He had spent six years staging Broadway revues, prioritising spectacle over steps—more interested in the movement of bodies in space than in precise footwork.

His first film, Whoopee! (1930) with Eddie Cantor, offered a testing ground. He experimented with overhead cameras, playful “parades of faces,” and chorus lines in ten‑gallon hats, creating cinematic illusions no stage could match. Musicals were already wobbling at the box office, but Berkeley’s experiments suggested that film could do something Broadway never could: turn human motion into pure visual magic.

“I’m Going Shopping with You” – Gold Diggers of 1935

Dick Powell and Gloria Stuart sparkle through a high‑spirited shopping spree in a visually inventive montage—an elegant example of Berkeley turning everyday life into cinematic flair.