Behind the Curtain: Busby Berkeley’s Collaboration, Innovation & Controversies

Berkeley's other side

Working with Studios, Dancers and Cameramen

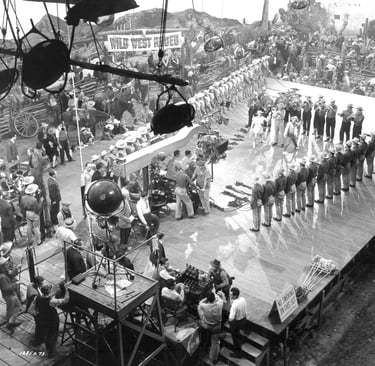

Busby Berkeley didn’t just choreograph for the screen—he choreographed the entire Hollywood machine. At Warner Bros., his human kaleidoscopes and surreal spectacles like 42nd Street and Footlight Parade were nothing short of a studio lifeline, earning him the nickname “Zanuck’s pet.” Yet with great budgets came great battles: studio executives adored his box office magic but fretted about his costly, time‑consuming methods. His move to MGM only sharpened these creative tensions, as his spectacle‑first instincts clashed with Arthur Freed’s preference for integrated musicals. By the time he reached 20th Century‑Fox and staged the delirious excess of The Gang’s All Here, Berkeley had secured his reputation as both saviour and scourge of studio patience.

Further Reading

The Million Dollar Mermaid by Esther Williams with Digby Diehl

Williams’ candid autobiography includes behind‑the‑scenes stories of working with Berkeley on her famous aquatic spectacles.

Buy it here

Ruby Keeler: A Photographic Biography by Nancy Marlow‑Trump

The story of one of Busby Berkeley’s most frequent on screen collaborators.

Buy it here

Brazilian Bombshell: The Biography of Carmen Miranda by Martha Gil‑Montero

Gil‑Montero offers a gripping account of Miranda’s experiences filming The Gang’s All Here, revealing Berkeley's loose approach to cast safety.

Buy it here

Watch

This Warner Archive showcase brings us Berkeley's most extravagant and imaginative musical numbers. From kaleidoscopic chorus lines to surreal visual fantasies, this clip captures the essence of the Berkeley style explored throughout this blog — a fusion of precision, glamour and cinematic innovation that defined the golden age of the Hollywood musical.

Controversies

Berkeley’s career glittered with innovation but was shadowed by controversy, scandal and a growing sense of artistic anachronism. In 1935, he was involved in a fatal car crash that led to three murder charges, two hung juries, and a high‑profile acquittal financed by Warner Bros., though public opinion remained unforgiving. His personal life was turbulent: six short‑lived marriages, heavy drinking and a dramatic suicide attempt after his mother’s death fed Hollywood gossip columns and studio anxieties alike. Professionally, he became infamous for grueling rehearsals and a “fascist” precision that pushed dancers to the brink—Judy Garland compared working with him to being “lashed with a bullwhip.” His spectacles, though dazzling, drew increasing criticism: numbers like Goin’ to Heaven on a Mule was full of racist caricature and minstrelsy, while sequences such as Lady in the Tutti‑Frutti Hat flirted with Freudian excess, courting censorship and scandal. As Hollywood shifted toward integrated musicals, Berkeley’s free‑floating visual fantasies began to feel excessive, even archaic and his attempts at full‑length direction were often dismissed as narratively weak. By the 1940s, he was both celebrated as a genius of cinematic spectacle and criticised as a limited artist whose brilliance shone brightest within the narrow, glittering world he created.

Technical Challenges and Problem‑Solving

If it moved, Berkeley could choreograph it. He pioneered overhead camera shots, mirrored floors, neon lighting, and revolving platforms to create the hallucinatory spectacles that made his name. Disembodied orchestras of 86 women’s arms, chorus girls blossoming into human fountains and entire sets built as optical illusions all became hallmarks of his work. Yet even in moments of constraint, he found elegance in simplicity. All’s Fair in Love and War, with its winking “battle of the sexes,” proves that Berkeley could conjure visual delight without the price tag of a waterfall. His motto said it all: “If it looks good, feels good, and sounds good—shoot it.”

Cameramen & Crew Collaborations

Berkeley’s true dance partner was his camera. He preferred to shoot his sequences linearly, often with a single camera, each shot pre‑planned to the millimetre. His crews watched in awe—and sometimes terror—as he orchestrated cranes, lighting and sound in perfect harmony. Miniature dolls on hooks, his “hanging the dollies” technique, mapped every formation before the dancers even stepped onto set. Cinematographer Sol Polito and sound engineer George Groves became his silent collaborators, enduring both bursts of encouragement and volcanic tirades in the quest for perfection.

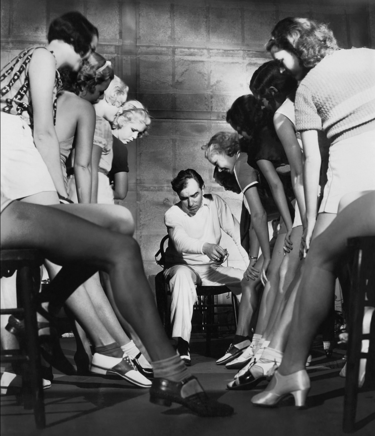

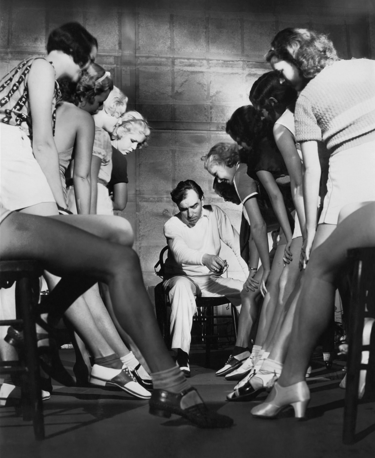

Demanding Dancer Relations

For dancers, a day with Busby Berkeley was part boot camp, part dream factory. Precision trumped artistry: he famously cared more about “beautiful knees” than ballet technique. Rehearsals stretched to exhaustion, with Esther Williams broke her neck in his aquatic ballet, Howard Keel broke a leg on horse back and Judy Garland called him “strange” while conceding his genius. Men in his troupes often became living set pieces—operating props, forming human arches, and spinning in synchronised tableaux to bring his cinematic visions to life. The result was pure magic on screen, but it left a wake of sore muscles and frayed nerves behind the camera.

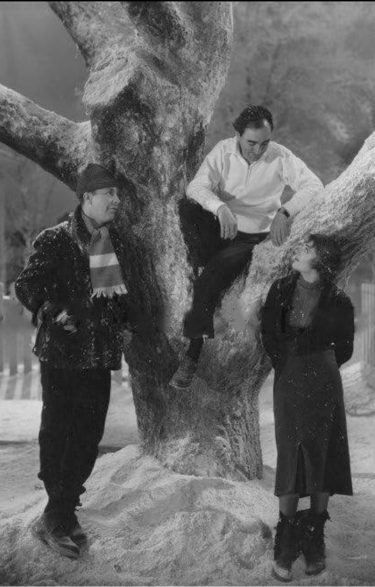

Ruby Keeler shares her memories of Footlight Parade in this brief TV interview with Tom Hatten, offering a rare glimpse into the world behind Busby Berkeley’s dazzling spectacles. Her reflections bring a human perspective to working with Berkeley's demanding precision and spectacle.