Busby Berkeley’s Hollywood Eras: From Warner Bros. Glory to the Changing Tides of Musical Cinema

Berkeley's changing style

Busby Berkeley’s career was a kaleidoscope in motion—glittering, restless and forever shifting. He rose to fame in the early 1930s as the master of cinematic spectacle, transforming Depression-era musicals into shimmering escapes of light, movement and fantasy. But Berkeley’s journey was no straight line. From the lavish Warner Bros. years to his more restrained MGM experiments and finally to the pared-back spectacles of his later career, his story mirrors the evolution—and eventual fading—of the Hollywood musical itself.

Further Reading

Era 1: Hollywood Be Thy Name: The Warner Bros. Story by Cass Warner Sperling & Cork Millner, with Jack Warner Jr.

This studio history sets the stage for Berkeley’s early triumphs, showing how his work helped rescue Warner Bros. from Depression‑era collapse.

Buy it here

Era 2: Life’s Too Short by Mickey Rooney

Rooney’s autobiography offers a front‑row view of Berkeley’s “gun‑for‑hire” years at MGM.

Buy it here

Era 3: The Million Dollar Mermaid by Esther Williams with Digby Diehl

Williams’ memoir captures the highs and hazards of Berkeley’s late‑career water ballets.

Buy it here

Watch Berkeley’s Evolution

Footlight Parade’s By A Waterfall is Berkeley at his zenith: a human waterfall of chorus girls, overhead kaleidoscopes and fluid camera movement. Here spectacle towers over story: the water ballet exists to astonish, even at the expense of narrative logic.

Why Did Berkeley’s Style Change?

Berkeley’s evolution was shaped by the studios, the times and his own ambitions. Warner Bros. had given him the freedom to create pure spectacle, but MGM and Fox demanded integration, story logic and efficiency. The musical genre itself was moving toward intimate, character-driven storytelling, while the economic realities of wartime and postwar Hollywood clipped the wings of excess.

Berkeley also longed for recognition as a serious director, venturing into dramas and comedies with mixed success. Over time, the “Berkeleyesque” brand—overhead kaleidoscopes, gliding cameras, human sculptures—became a nostalgic signature rather than a forward-looking style.

Era 3: Later Hollywood Work & the Decline of Signature Style

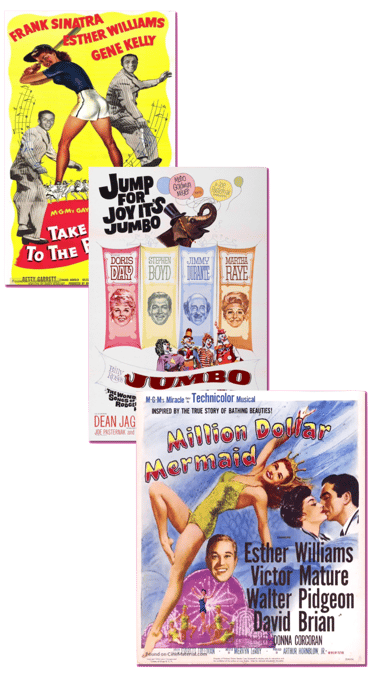

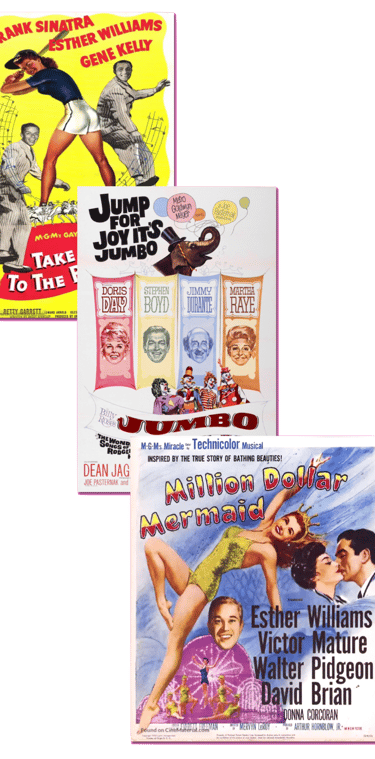

By the late 1940s, Berkeley’s world had changed and so had the musical. His later films—Take Me Out to the Ball Game (1949), Million Dollar Mermaid (1952), and Jumbo (1962)—show a master working within tighter creative and financial constraints.

The vast overhead formations and cascading kaleidoscopes gave way to shorter, simpler, more theatrical numbers. His later work often relied on monolithic visual ideas rather than the layered complexity of his Warner Bros. heyday. Legal troubles, personal losses, and the genre’s gradual decline all weighed heavily on him, and the studio system no longer had the appetite—or the budgets—for his most extravagant visions.

And yet, flashes of genius persisted. Million Dollar Mermaid’s water ballets, shimmering with geometric elegance, remind us that even in a muted form, Berkeley’s artistry could still astonish.

Era 2: Post-Warner Transitions and the “Gun for Hire” Period

By the late 1930s, Berkeley’s golden period at Warner Bros. had dimmed. Studio head Jack Warner refused his salary demands and Berkeley moved on, taking his talents to MGM—home of Arthur Freed’s newly dominant integrated musicals. Here, spectacle had to bend to story, and Berkeley’s flights of fantasy were hemmed in by narrative logic.

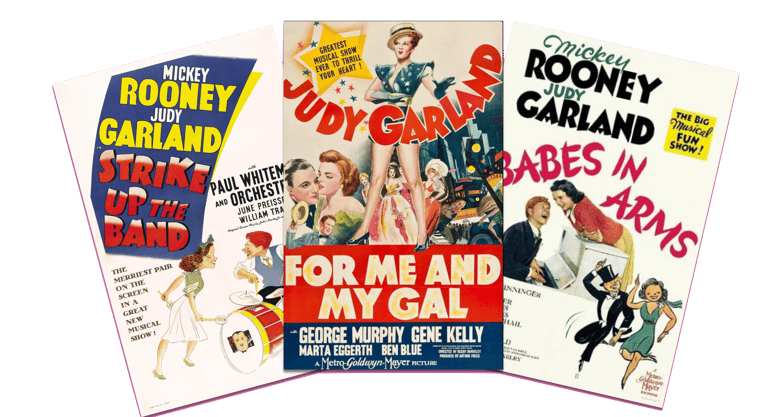

At MGM, his work on films like Babes in Arms (1939), Strike Up the Band (1940) and his personal favorite, For Me and My Gal (1942), showed flashes of his brilliance—though in smaller, more intimate packages. Gone were the endless kaleidoscopes; instead, numbers were designed to showcase stars like Judy Garland and Mickey Rooney. His brief stint at 20th Century-Fox with The Gang’s All Here (1943) let him off the leash again, and Berkeley created a Technicolor dream of giant bananas and explosive, surreal choreography.

This middle period was shaped by shifting tastes, budget pressures, and the Production Code’s dampening of his pre-Code risqué flair. Audiences increasingly favored integrated, story-driven musicals, leaving Berkeley’s grand, disconnected spectacles feeling—at times—anachronistic.

Era 1: The Warner Bros. Golden Age (Early 1930s)

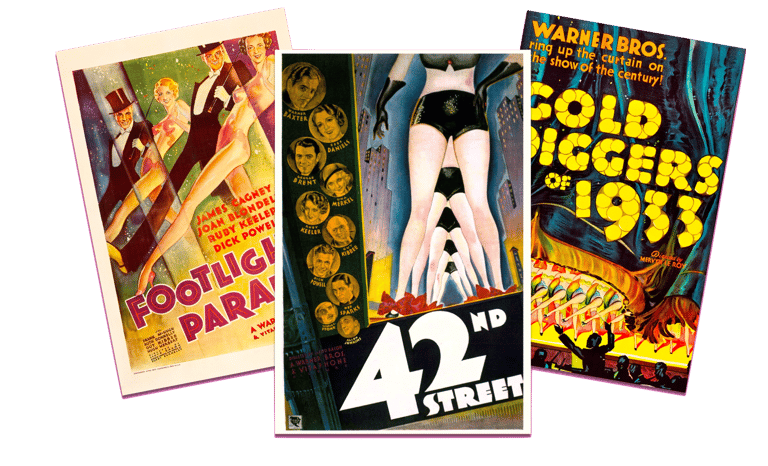

The early 1930s were Berkeley’s kingdom and Warner Bros. was his palace. Films like 42nd Street (1933), Gold Diggers of 1933 and Footlight Parade gave him near-total freedom to reimagine what a musical could be. Narrative often took a backseat to showstopping numbers—entire worlds blossomed in the space of a single song.

His signature style defined this era: human kaleidoscopes seen from dizzying overhead shots, dancers spinning into circles, triangles and geometric blooms on reflective black-and-white floors. Cameras slithered between legs, plunged from chandeliers and zoomed from a single face to a skyline. He built surreal landscapes of colossal coins, neon violins and endless staircases, often stacking locations and movements into dreamlike crescendos. In the midst of Depression-era grit, these spectacles felt like impossible worlds—dazzling escapes that belonged to the screen alone.

Nearly two decades later, Berkeley returned to the theme in Million Dollar Mermaid (1952) with a refined version of his aquatic fantasy. Esther Williams glides through synchronised pools and mirrored sets—but this time, the movement supports narrative tension, grounded in character and story rather than pure spectacle.