Busby Berkeley’s Enduring Legacy: How His Vision Transformed Film & Pop Culture

Berkeley's legacy

Busby Berkeley wasn’t just a dance director — he was a cinematic revolutionary who catapulted the movie musical into an art form all its own. At a time when Hollywood musicals were still tied to the stage, Berkeley unleashed the camera, sending it soaring over kaleidoscopic chorus lines and diving through impossible geometries. His legacy is not merely in the glitter or the overhead shots, but in how he taught film to dance. In this post, we explore how Berkeley’s radical vision influenced generations of filmmakers, choreographers and pop culture creators — and why his work still captivates audiences nearly a century later.

Influence on Later Directors, Choreographers, and Music Videos

Tearing Down the Proscenium Arch

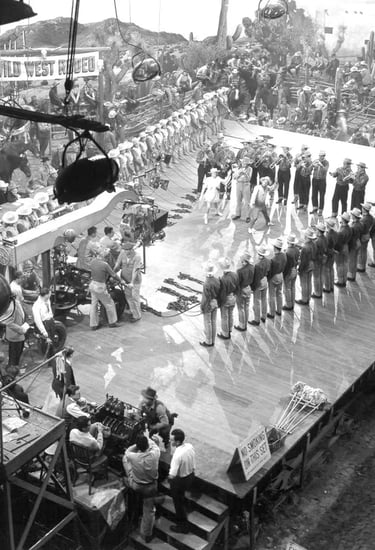

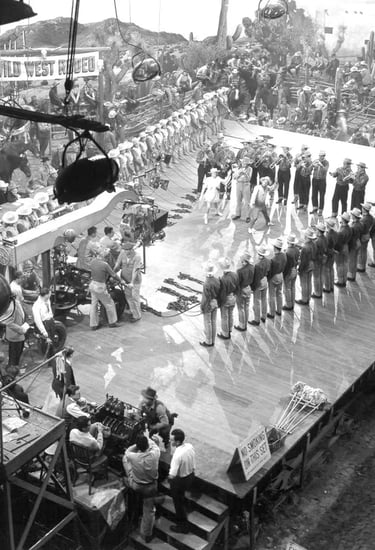

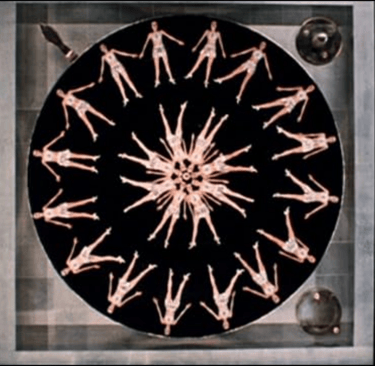

Berkeley’s true innovation was in understanding that film could do what the stage could not. He tore down the imaginary proscenium arch, choreographing the camera as much as the dancers. Sweeping crane shots, dizzying overheads, and intricate editing turned movement into pure cinematic language. Suddenly, dance sequences were no longer mere stage reproductions; they became visual symphonies designed for the screen.

Inventor and Craftsman

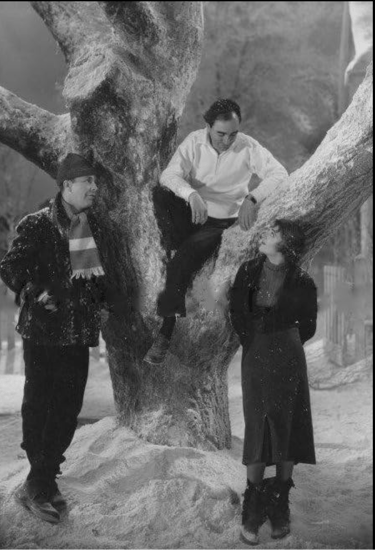

To watch a Berkeley number is to see an engineer at play. He turned pianos dodgems, transformed dancers into city skylines and scuulpted arches of continuous legs for his camera to snake beneath. He was dance director, set designer, cinematographer and editor all in one — a single, restless imagination translating music into moving architecture.

Inspirations & Imitations

Berkeley’s influence rippled far beyond his own era. Gene Kelly famously credited him as his “chief teacher,” acknowledging that Berkeley had shown him what a movie camera could do for dance. Even Leni Riefenstahl admired the precision and mass choreography of his regimented ensembles — though Berkeley’s intent was escapist fantasy rather than propaganda. Directors from Vincente Minnelli to Ken Russell borrowed his visual bravura, but few matched his alchemy of geometry, spectacle and cinematic timing.

References in Film

Berkeley’s style has become cultural shorthand. Say “Busby Berkeley,” and most people picture glittering chorines spinning in impossible kaleidoscopic formations. His influence is immediately legible in:

Mel Brooks’s The Producers (1968) — where a few quick overhead formations parody him perfectly.

Ken Russell’s The Boy Friend (1971) — a love letter to the grandiose, dreamlike Berkeley touch.

Herbert Ross’s Pennies from Heaven (1981) — whose fantasy sequences evoke Depression-era escapism straight from Berkeley’s playbook.

The Great Muppet Caper (1981) — proving his style is now as much part of family entertainment as film history, with the Muppets’ own Berkeleyesque fantasies playing for comic charm.

The Big Lebowski (1998) — its bowling-alley dream sequence is a gleeful homage to his surreal, floating camera worlds.

Even in commercials, opening credit sequences and music videos, the “Berkeleyesque” aesthetic — geometric formations, oversized props and swooping camera moves — remains an instantly recognisable visual language.

Why He Remains Relevant and Inspiring Today

Unforgettable Spectacle & Escapism

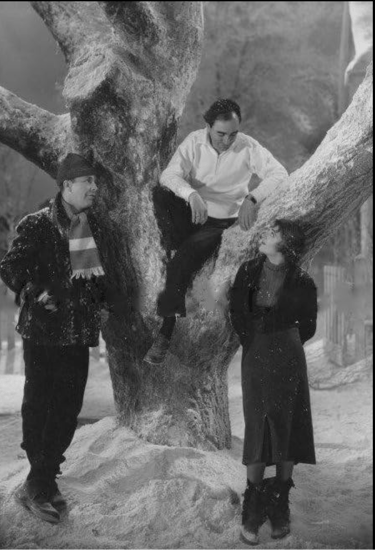

In the teeth of the Great Depression, Berkeley offered audiences glittering dreamscapes on a scale reality could never deliver. Whether it was chorines floating in a pool like living lilies or giant coins spinning through a stage, his numbers were pure escapism — a dazzling antidote to economic despair.

Artistic Vision & Film Mastery

What sets Berkeley apart is not just scale, but invention. He made the camera a partner in the dance, a fluid observer that could swoop, plunge and pirouette. He transformed musical numbers into visual poems, balancing playful excess with unexpected poignancy.

The Enduring “Berkeleyesque” Style

Today, “Berkeleyesque” describes a specific cinematic magic: regimented chorus lines, geometric aerial shots, fantastical props, and a sense of scale that borders on the surreal. His work is still quoted, parodied and celebrated because it feels both nostalgic and timeless. Beneath the spectacle, his numbers tapped into something universal — the need for beauty, fantasy and movement in perfect harmony.

Watch: Busby Berkeley Style & Aqueous Spectacle

Eleanor Powell – “Fascinatin’ Rhythm” (Lady Be Good, 1941)

A breathtaking Berkeley‑directed tap routine featuring Powell dancing between a cascade of boogie-woogie pianos in precise, show‑stopper formation. Whilst the rhythm and precision are quintessential Berkeley, he never had a better dancer at the centre of a routine.

Esther Williams Aquatic Spectacle – Easy to Love (1953)

Featuring the iconic Cypress Gardens water‑ski finale choreographed by Busby Berkeley. Hundreds of synchronised swimmers and skiers combine into vibrant, flowing formations that channel his aquatic kaleidoscopes. Technicolor at its most opulent.

Further Reading

Buzz: The Life and Art of Busby Berkeley by Jeffrey Spivak

A rich and engaging biography exploring Berkeley’s life, innovations and contradictions.

Buy it here

Showstoppers: Busby Berkeley and the Tradition of Spectacle by Martin Rubin

A look at Berkeley’s visual style and its place in musical and cinematic history.

Buy it here

Hollywood Musical by Jane Feuer

A concise and brilliant look at how spectacle functions in the Hollywood musical, including Berkeley's influence.

Buy it here

Navigation Links

← Part 6: Busby Berkeley’s Hollywood Eras: From Warner Bros. Glory to the Changing Tides of Musical Cinema

→ Part 8: Final Reflection: Why Busby Berkeley Still Matters