Final Reflection: Why Busby Berkeley Still Matters

Berkeley's legacy

Nearly a century on, Busby Berkeley’s kaleidoscopic spectacles still shimmer across screens and imaginations. His musical numbers—half cinematic sorcery, half dreamscapes —remain a reminder that Hollywood, even in its darkest Depression years, could conjure a glittering escape hatch. But what makes this dance director’s work endure long after the last chorus girl hung up her tap shoes? Let’s look at Berkeley’s genius, his influence on film musicals, and why his visual vocabulary continues to inspire today’s filmmakers, from Ken Russell to the Coen Brothers.

Further Reading

Buzz: The Life and Art of Busby Berkeley by Jeffrey Spivak

A rich and engaging biography exploring Berkeley’s life, innovations, and contradictions.

Buy it here

Showstoppers: Busby Berkeley and the Tradition of Spectacle by Martin Rubin

A deep dive into Berkeley’s visual style and its place in musical and cinematic history.

Buy it here

Enduring Popularity and Influence

Even now, Busby Berkeley’s name is shorthand for extravagant spectacle. His work in Footlight Parade, Gold Diggers of 1933, and Dames dazzled Depression-era audiences with pure escapism, but its influence radiates far beyond classic Hollywood.

Busby Berkeley’s visual DNA still ripples through popular culture, from music videos to musicals to commercials. His kaleidoscopic choreography and overhead precision live on in The Big Lebowski’s dream sequence, Disney’s “Be Our Guest” in Beauty and the Beast, and Janet Jackson’s playful 1990 street‑scene “Alright.” Even animated shows like The Simpsons and Family Guy, as well as Martin Scorsese’s New York, New York, borrow his signature “Berkeleyesque” style—proof that nearly a century later, his geometric spectacle remains instantly recognisable and endlessly imitated.

Berkeley didn’t just choreograph dance—he choreographed wonder. His vision lifted musical cinema into the realm of dreams, where hundreds of synchronised bodies could become a single, shimmering idea.

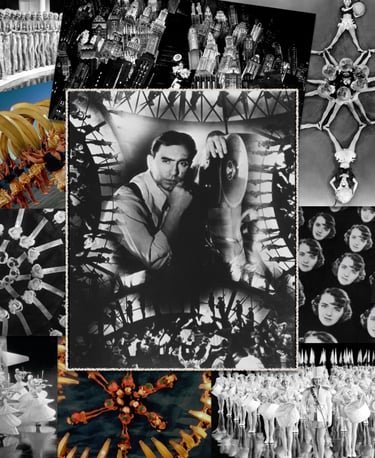

Artistic Vision Beyond Dance Steps

For Berkeley, choreography was never simply about steps. He called himself a “dance director”, and his true stage was the camera lens.

He envisioned formations and camera paths in his “mind’s eye,” often using miniature figurines on hooks—his famous “hanging dollies”—to map movements before putting dancers on set. Music wasn’t just background; it was the architectural blueprint for visual design.

What he created couldn’t be translated back to the theatre. His genius was pure cinema, transforming bodies and space into something audiences had never seen before.

Saving Warner Bros. — One Dance Number at a Time

By 1933, Warner Bros. was financially gasping. Then along came 42nd Street. Berkeley’s show-stopping numbers electrified audiences and rescued the studio from the brink of bankruptcy.

These sequences weren’t just artistic experiments—they were box office gold, proving that spectacle could be both critically lauded and commercially vital. Hollywood learned that even in hard times, audiences would flock to marvels they’d never see on stage. Berkeley gave Depression-era moviegoers hope, fantasy, and a reason to queue around the block.

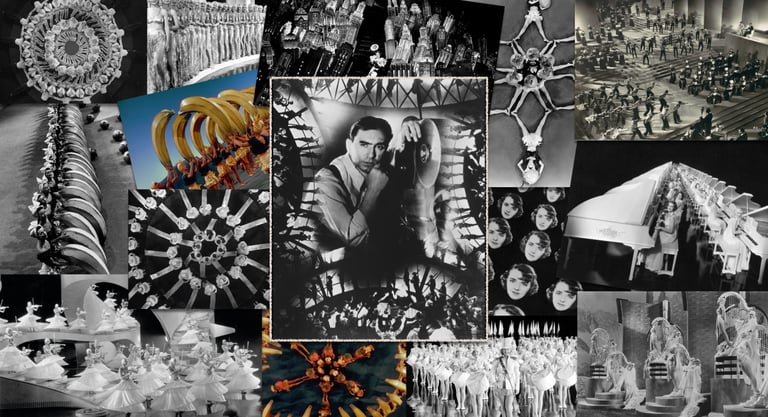

The “Berkeleyesque” Visual Signature

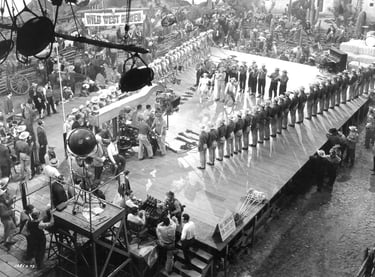

To say a musical number is “Berkeleyesque” is to invoke a world of audacious spectacle. His hallmarks include:

Regimented chorus lines forming hypnotic geometric patterns.

Kaleidoscopic overhead shots—dancers spinning into flowers, pinwheels or starbursts.

Extravagant camera moves: cranes diving through legs, zooms into eyes that dissolve into cityscapes.

Stylised use of the female form, often as abstraction—arms, legs, and faces forming living ornaments.

Giant props—coins, pianos, fountains—that become performers in their own right.

Seamless transitions between the intimate and the epic, the earthly and the dreamlike.

Berkeley’s work turned the screen into a fantastical playground where the laws of gravity, scale and narrative could bend to his imagination.

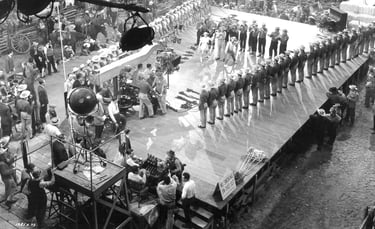

Revolutionising the Musical Film Genre

Busby Berkeley didn’t just choreograph movement —he choreographed the camera itself.

Before Berkeley, musicals were largely proscenium-bound, with static shots capturing stage-like movement. Berkeley blasted past those constraints. As Gene Kelly once said, he “tore away the proscenium arch,” unleashing a cinematic musical where the lens itself danced, swooped and spiraled through space.

His overhead shots transformed chorus lines into living mandalas; his crane work floated audiences into impossible vistas. Numbers like By a Waterfall (Footlight Parade, 1933) weren’t just performances—they were visual symphonies, designed to be experienced only on film.

Watch: Busby Berkeley’s Legacy

These two gloriously self‑aware homages are Berkeley's big screen legacy. In the Coen brothers’ Big Lebowski (1998), the Dude drifts into a surreal bowling dreamscape where he floats under a tunnel of sequinned legs and tumbles through a kaleidoscope of showgirls. It’s pure Berkeley: overhead geometries, hypnotic symmetry and oversized props.

Meanwhile, in The Great Muppet Caper (1981), Miss Piggy’s poolside fantasy sweeps her into a riot of synchronised swimmers, top‑down choreography and dreamy, glittering spectacle. It’s Berkeley by way of Henson, right down to the water‑borne patterns that echo By a Waterfall from Footlight Parade.

What’s striking is that in both cases, these Berkeleyesque routines are framed as fantasies. No one in the “real” world is watching; the numbers exist only in the characters’ minds. This underlines how audiences now instinctively associate Berkeley’s kaleidoscopic excess with dream logic and escapism—moments when reality briefly yields to pure, cinematic wonder.

It’s also worth noting that neither sequence achieves the razor‑sharp precision of Berkeley’s original creations.