Lorenz Hart Part Five: When Rodgers Moved On: How Oklahoma! Left Larry Hart Behind

How a new era in the stage musical left Hart behind

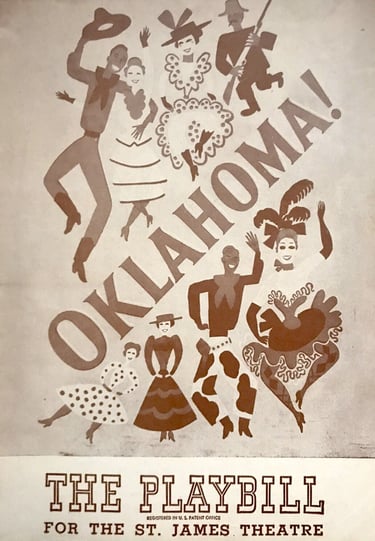

November 1943. At one end of town, the revival of A Connecticut Yankee was playing — a bittersweet curtain call for Lorenz Hart, the lyricist who had turned heartbreak into rhyme. Across the city, at the St. James Theatre, a very different crowd was gathering for performances of Oklahoma! — all sunlit prairies and moral clarity. Between them stretched an invisible divide: irony on one side, innocence on the other. That night, Richard Rodgers crossed it. And Larry Hart, the small man with the large soul, was left behind.

Their songs had reached the summit of sophistication. Babes in Arms, Pal Joey, The Boys from Syracuse — all dazzling, cynical, urbane. But success masked a deepening fault line. Hart, always small in stature, seemed to shrink further under the weight of loneliness. His homosexuality, his insecurity, his increasing dependence on alcohol — all conspired to make him unreliable. And Rodgers, a man who believed in punctuality almost as much as melody, began to look elsewhere for stability.

The Poet of Manhattan

When they first met in 1919, Rodgers was sixteen — all polish and punctuality — and Hart, twenty-three, already looked slightly unbuttoned by life. He was compact, quick-witted, and brimming with ideas. Every rhyme carried both laughter and loss, every melody an undercurrent of longing. To hear Hart’s lyrics was to walk through a world where love could break your heart and make you grin in the same breath.

“Corny,” He Said

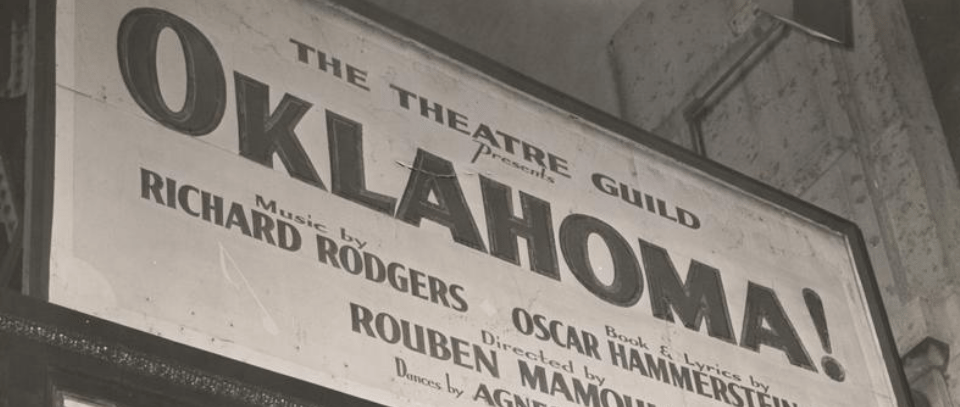

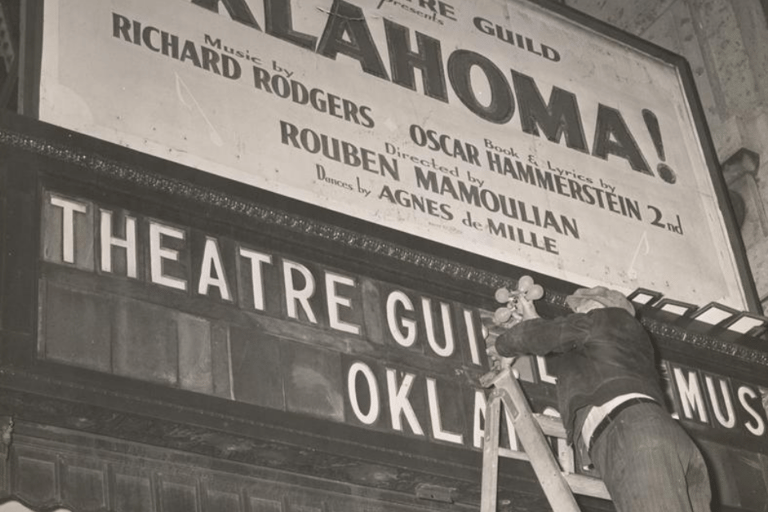

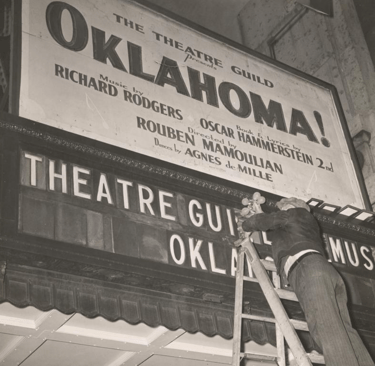

Then came Green Grow the Lilacs — an obscure play about farm folk and sunshine, proposed by the Theatre Guild in 1942. Rodgers saw potential; Hart saw hay bales. “Corny,” he declared, preferring a Mexican holiday to another deadline. So Rodgers made the decision that would change Broadway forever.

He turned to Oscar Hammerstein II — a lyricist from the old guard, known for sincerity, moral clarity, and rhymes that didn’t wink at you. Hammerstein was everything Hart was not: dependable, un-ironic.

Their collaboration produced Oklahoma! — a musical that replaced the smoky jazz club with the open prairie, and the wisecrack with the anthem.

The Night of Two Worlds

Hart came to the opening. Rodgers was resplendent beside his new partner; Hammerstein, calm and dignified, basked in applause. Somewhere in the back, Hart clapped too — polite, bewildered, the old world congratulating the new. The man who’d made Broadway witty watched as it grew wholesome. One critic later called it “the night irony gave way to innocence.”

Three nights later, Hart was dead of pneumonia.

From Manhattan to the Meadow

The contrast between Rodgers’ two lyricists is almost mythic. Hart’s world was nocturnal — cocktails, neon, and lovers who lied beautifully. Hammerstein’s was agrarian — wheat fields, courtship and moral clarity you could hum along to.

Where Hart wrote about loneliness, Hammerstein wrote about belonging. Hart’s love songs sparkled with doubt; Hammerstein’s glowed with faith.

Rodgers, ever the pragmatist, adjusted his compass. The collaboration with Hammerstein was everything Broadway had been waiting for: story-driven, emotionally direct, wholesome enough for middle America but crafted with metropolitan skill. Oklahoma! ushered in the Golden Age of the musical — but it also buried the smoky, jazz-soaked wit that had defined the Rodgers & Hart years.

A Quiet Farewell

While Rodgers and Hammerstein rode the bright wave of Oklahoma!, Hart’s final act played out in minor key — A Connecticut Yankee, revived but faintly out of time. His last lyric, To Keep My Love Alive, was a masterclass in black comedy: a roll call of murdered husbands sung with sparkling venom.

He left the theatre that night unwell, walked into a cold New York rain, and within days was gone.

The Echo That Lingers

If Hammerstein’s musicals were sunrise, Hart’s were twilight — and we need both to understand the day. The world may have moved on from Hart’s brand of wit and woe, but the emotional intelligence he brought to the American songbook still shapes it. Without him, the so-called Golden Age would lack the shadow that gives it depth.

Watch

Before you watch: these videos are official releases and still live at time of posting.

"Rodgers and Hart Write a Song” – Makers of Melody (1929)

Watch Rodgers and Hart at work in this rare short film, capturing the pair’s quicksilver wit and effortless collaboration at the dawn of the sound era.

Further Reading

Broadway Babies: The People Who Made the American Musical by Ethan Mordden

A lively chronicle of Broadway’s pioneers, highlighting how Rodgers and Hart’s Pal Joey and The Garrick Gaieties transformed musical storytelling.

Buy it here

Lorenz Hart: A Poet on Broadway by Frederick Nolan

The definitive biography of Hart, tracing his lyrical genius, personal struggles, and the modern wit that redefined Broadway songcraft.

Buy it here

Make Believe: The Broadway Musical in the 1920s by Ethan Mordden

Explores the birth of the modern musical, with The Garrick Gaieties and “Manhattan” marking Hart’s arrival as the voice of a new, sophisticated age.

Buy it here

Musical Stages: An Autobiography by Richard Rodgers

Rodgers’s own reflections on his collaborations, offering candid insight into his creative partnership with Lorenz Hart.

Buy it here

Popular Music in the 1930s by Arnold Shaw

Charts the evolution of American popular song during the Depression, with Hart’s urbane melancholy and lyrical precision central to the era’s changing sound.

Buy it here

Explore the Series

← Part 4: Pal Joey and the Dark Edge of the Musical

[End of Series]

“Blue Moon: The Story Behind the Song” – Songbook Station with Edward Barnes

Trace the evolution of “Blue Moon” from discarded drafts to enduring standard, tracing Hart's brilliant lyrical reinvention.