Who Was Busby Berkeley? The Maestro Who Turned Chorines into Cinematic Art

Introduction to Busby Berkeley

Introduction to Berkeley

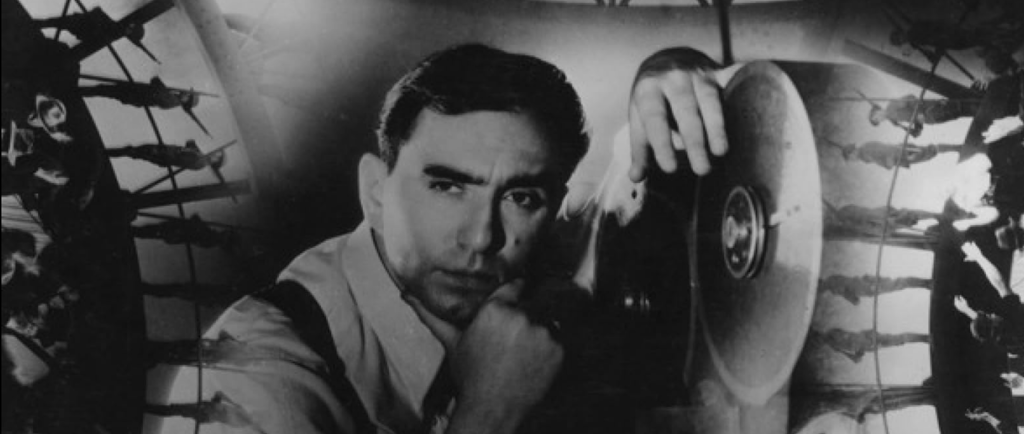

Busby Berkeley wasn’t a choreographer as we understand the term — he was a visionary film dircetor who redefined what movement could mean on screen. This series explores Berkeley’s life, decodes his revolutionary style and reveals how the most iconic images in Hollywood musicals—the blueprint for a thousand tributes, the instant cue that 'a musical moment is happening'—first burst into being.

Early Life and Formative Years

Busby Berkeley was born Busby Berkeley William Enos in Plattsburgh, New York, in 1895. “Busby” was in honour of family friend and actress Amy Busby. “Berkeley” came from his mother’s stage name — Gertrude Berkeley. “William” paid tribute to actor William Gillette, who was a family friend and the first man to play Sherlock Holmes on stage. “Enos” came from father Frank Enos, an actor and director.

Frank died when Berkeley was just eight, but his mother Gertrude remained a guiding force throughout his life. During World War I, Berkeley enlisted into the army and became Second Lieutenant Enos. It was in the training camps, among boots and mud, that the future began to take shape. Tasked with organising military drills, he began experimenting with regimented marching and “trick drills” (stylised marching routines with intricate patterns): human geometry at scale. The seeds of his cinematic style — precision, symmetry, and spectacle — were planted on the parade ground.

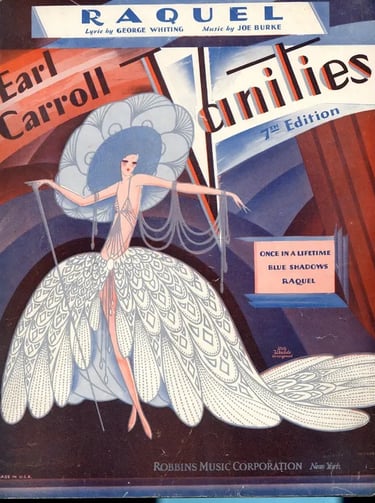

Although he had no formal dance training, Broadway embraced him as a “dance director,” a role focused less on steps and more on rhythm and showmanship. Berkeley wanted movement that dazzled. After early stage successes with A Connecticut Yankee (1927) and the lavish Earl Carroll Vanities (1928), his signature began to emerge: well drilled ranks, visual excess and grandeur.

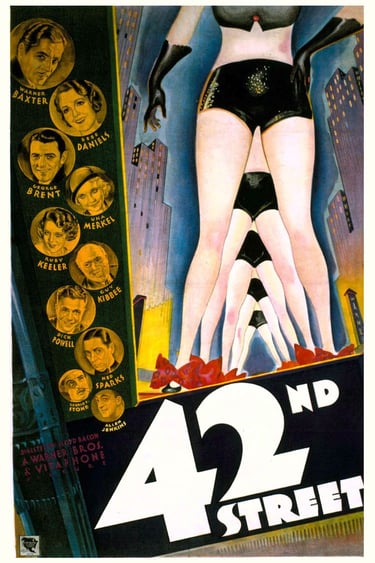

His breakthrough came in 1933 at Warner Bros., when Darryl F. Zanuck entrusted him with the musical sequences for 42nd Street. Zanuck showed his confidence in Berkeley by declaring: “Give Berkeley whatever he wants.” As Warner Bros. was a studio that prized spectacle over star power, Berkeley had the perfect opportunity to develp his visionary style.

Why Busby Berkeley is a Seminal Figure

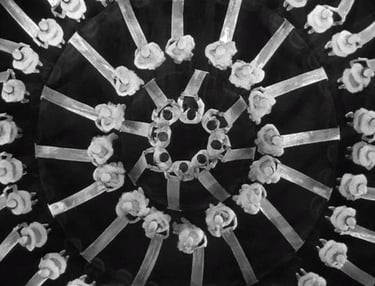

He Made the Camera Dance: As Gene Kelly said, Berkeley didn’t film stage choreography—he created for the camera, using crane shots, overhead views and innovative editing to build mesmerising visual designs.

The “Berkeleyesque” Style:

Berkeley's style revived a fading stage tradition and became a permanent part of the cultural vocabulary. From 42nd Street and Gold Diggers to The Gang’s All Here, his visual language continues to inspire film, TV, and music videos. But what is it?

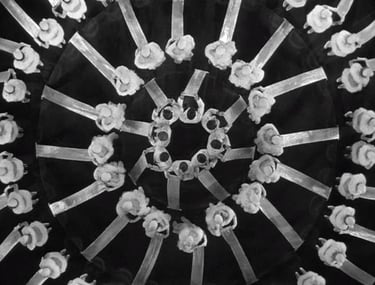

Massed chorus lines in regimented, kaleidoscopic geometric patterns

Lavish sets, giant props and hallucinatory camerawork

Use of the female form as abstract shapes

Voyeuristic “no-men-allowed” spaces that were playful yet provocative

Spectacle Over Story: Berkeley’s numbers often existed outside the narrative, stacked as grand finales or standalone “showstoppers,” providing dazzling escapism especially vital during the Depression.

Watch

Still live at time of posting — witness Berkeley’s kaleidoscopic magic come to life:

42nd Street (1933) – “I’m Young and Healthy”

Given three revolving platforms, Berkeley famously remarked, “Now I’ve got them—what am I going to do with them?” The result was a dazzling display of rotating choreography, where dancers spiral and glide in perfect sync—a prime example of Berkeley turning logistical challenges into visual marvels.

Gold Diggers of 1933 – “The Shadow Waltz”

Reflective floors, neon violins, and surreal transformations—a hallmark Berkeley spectacle. This number floats between dream and design, with camera choreography that reimagines the stage as a shimmering, geometric wonderland.

Where to Begin with Busby Berkeley by Tom Huddleston

Perfect for newcomers: Hudson frames Berkeley’s most essential films, explaining how cinematic spectacle evolved in just a seven-minute routine.

Read it here

Buzz: The Life and Art of Busby Berkeley by Jeffrey Spivak

A rich and engaging biography exploring Berkeley’s life, innovations and contradictions.

Buy it here

The Movie Musical! by Jeanine Basinger

Basinger’s sections on the 1930s shine a spotlight on Busby Berkeley, unpacking his kaleidoscopic visual language and how his dreamlike numbers defined escapism during the Great Depression.

Buy it here

Explore the Series

[Start of Series]

→ Part 2: The Rise of Berkeley’s Signature Style: From Broadway to the Big Screen

Transition to Hollywood and Breakthrough

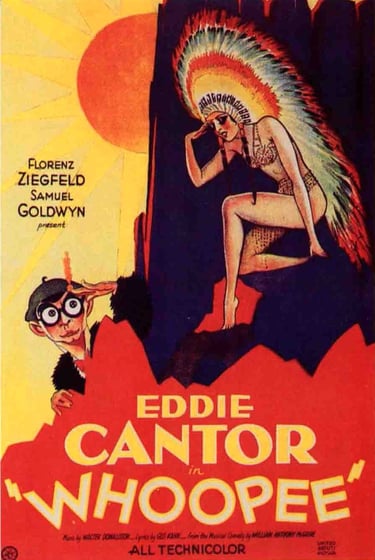

Berkeley’s film career began in 1930 with Whoopee!, produced by Samuel Goldwyn. It was during this production that he first started experimenting with camera angles and overhead patterns, laying the groundwork for his distinctive style.