Lorenz Hart Part Three: From Manhattan to Melancholy - Hart and the Sound of Modernity

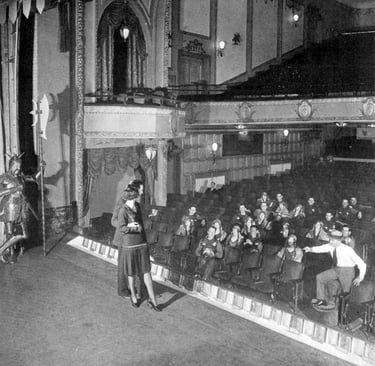

The Musical in the Jazz Age

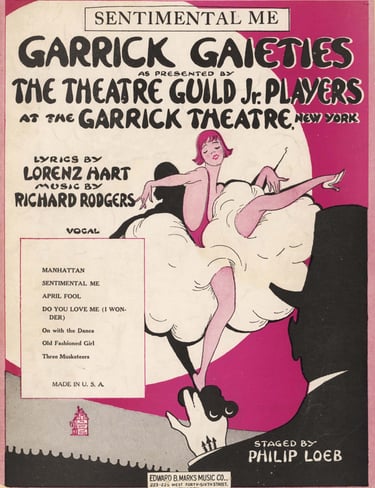

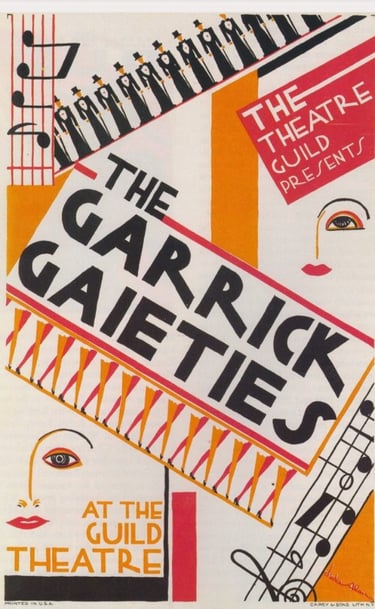

In 1925 the Garrick Gaieties introduced a song that would define the jazz-fuelled clatter of New York: “Manhattan.” Penned by a twenty-nine-year-old lyricist named Lorenz Hart and set to the music of the prodigiously talented Richard Rodgers, the number arrived like a perfectly timed taxi cab: witty, urbane, and unmistakably modern. Manhattan was an auditory snapshot of the Jazz Age itself, a deft swing between sophistication and rueful humour that would become Hart’s signature.

Rodgers and Hart: Structure Meets Mess

The partnership with Richard Rodgers, which began in 1919 when Hart was twenty-three and Rodgers just sixteen, was a study in contrasts. Rodgers was methodical, disciplined, commercially minded—a stabilising anchor. Hart, by contrast, drifted through life erratic, sensitive, often intoxicated, a mercurial spirit who lived in the city’s edges by night. Their collaboration was a balance of control and improvisation, intellect and sentiment, cynicism and yearning.

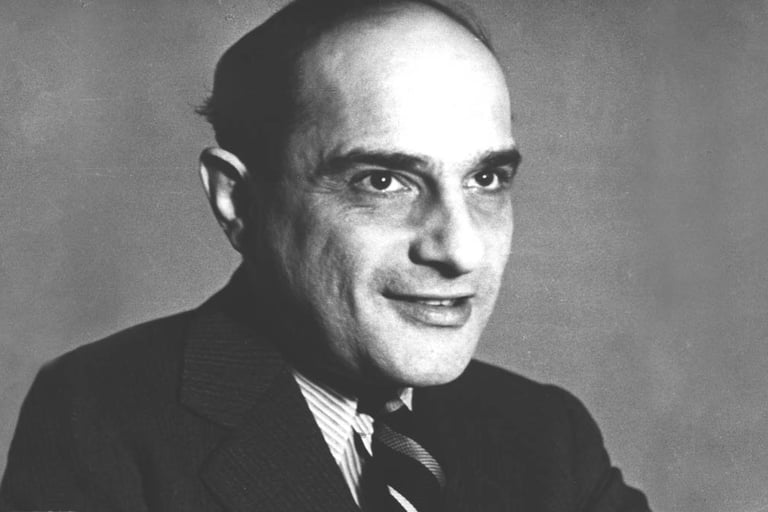

The Littlest Giant of Broadway

Lorenz Hart was born in 1895 in New York to Max and Frieda Hart, Jewish immigrants from Hamburg. He was barely five foot tall but possessed a towering intellect. Contemporary accounts describe him as “slightly gnomelike,” a figure whose small stature belied the emotional depth of his work. His homosexuality, coupled with chronic insecurity and fragile health, created a life tinged with personal torment, yet this very tension seemed to fuel the brilliance of his lyrics. Joshua Logan, the legendary director and friend, called him “the biggest little man I ever knew,” a phrase that captures both the impact of Hart’s artistry and the fragility of his being.

By the mid-1920s, Hart and Rodgers were pioneering what might be called “light-verse literacy” in popular song. Alongside contemporaries such as Ira Gershwin and Cole Porter, Hart elevated the lyric from a perfunctory placeholder in Tin Pan Alley ditties to a bona fide literary art form. His songs were intricate mosaics of rhyme and rhythm, verbal fireworks tempered with acute psychological insight. Manhattan, with its urbane wit and sly charm, exemplified this: a patter song that danced through unexpected rhymes, evoked the hum of city streets, and hinted at an undercurrent of longing. Hart’s melancholy shimmered just beneath the surface—a motif that would deepen as the optimism of the 1920s gave way to Depression-era realism.

Pushing the Boundaries of Broadway

Hart’s lyricism was never static. A Connecticut Yankee (1927) combined historical satire with contemporary idioms, while On Your Toes (1936) dared to integrate ballet into the musical narrative. Perhaps his most radical achievement was Pal Joey (1940), starring Gene Kelly, which broke away from conventional musical comedy by embracing morally ambiguous, cynical characters. Hart’s lyrics captured post-crash urban life with both seduction and sharp-eyed realism: the gloss of city living overlaying grit, charm masking opportunism, desire mingling with disillusionment. Joey Evans, suave and unscrupulous, was a mirror to the world Hart inhabited—charming, opportunistic, fundamentally human. Songs like I Could Write a Book and Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered encapsulated both the thrill of love and the sobering recognition of its imperfections.

Hart’s mastery extended beyond Broadway, too. His lyrics were nimble, internally sophisticated, and emotionally precise. He could pivot from playful inversion in My Funny Valentine—“Your looks are laughable, unphotographable”—to the profound despair of A Ship Without a Sail, reflecting the broader societal anxieties of the interwar period. Hart’s urbane wit allowed him to comment on social mores with a dual lens: irony and empathy intertwined. While Oscar Hammerstein II later emphasised the integration of words with plot and character, Hart demonstrated that lyrics alone could be an art form—rich, clever, and psychologically nuanced.

The Shadows Behind the Spotlight

Yet Hart’s genius was inseparable from his personal turmoil. Alcoholism increasingly impeded his professional life. By the early 1940s, the sparkle had dimmed: he spent long stretches in bed, haunted by drink, while Rodgers and Hammerstein’s ascendant works illuminated Broadway stages. Hart’s final years were marked by sorrow, isolation, and the stark contrast between his private despair and the public adulation he had long commanded. He died at forty-seven, mere days after a revival of A Connecticut Yankee opened.

Hollywood would sanitise this complexity. The 1948 MGM film Words and Music, starring Mickey Rooney, presented Hart’s life as a tidy, cheerful narrative, straightening out both his sexuality and his struggles with alcoholism. The dark undercurrents, the very qualities that gave his lyrics their resonance, were edited out, leaving a palatable, yet partial, picture of a man whose brilliance thrived on tension and contradiction.

Enduring Legacy

Hart’s work endured. Songs like Blue Moon, conceived in response to commercial pressures, became timeless standards, bridging stagecraft with popular music. Hart’s legacy is inseparable from the cultural transitions of his era: the electric vitality of the Jazz Age, the sobering realism of the Depression, and the emergence of the American musical as a sophisticated, emotionally resonant art form.

Hart occupies a pivotal place in the American musical landscape. His lyrics captured not just the rhythms of city life but the psychology of the urban century: its lightness and weight, its exhilaration and melancholy. Hart bridged the flippancy of the 1920s with the realism of the 1930s, prefiguring the integrated musical forms that Rodgers and Hammerstein would later perfect.

Despite the overshadowing of Rodgers-Hammerstein’s later dominance, Hart’s influence resonates through generations. From Lionel Bart to Stephen Sondheim, lyricists acknowledge the debt owed to Hart’s intricate rhymes, sophisticated humor, and emotional depth. His uncanny ability to make audiences laugh and cry in a single verse remains unmatched. Revisiting Manhattan, My Funny Valentine, and Blue Moon, one appreciates the rare blend of intellect, sentiment, and urban sensibility that defined both the man and the age he chronicled.

Lorenz Hart's lyrics immortalised urban vernacular, wit and melancholy, blending light-verse precision with jazz-inflected rhythms and psychological nuance. From the bustling streets of Manhattan to the haunting longing of A Ship Without a Sail, Hart’s songs span eras and sensibilities: exuberant yet reflective, glamorous yet gritty. He was a poet of the city, a master of language, and a figure whose personal struggles only deepened the resonance of his work. Through his songs, the rhythms of Manhattan — complex, vibrant, and tinged with melancholy — continue to echo across Broadway and beyond.

Watch

Before you watch: these videos are official releases and still live at time of posting.

“Manhattan” – Words and Music (1948)

Elegant, witty, and urbane — 1920s New York captured in song.

Further Reading

Make Believe: The Broadway Musical in the 1920s by Ethan Mordden

A lively account of Broadway’s golden decade, charting how musical theatre evolved from revue to narrative form. Mordden captures the cultural ferment that gave rise to The Garrick Gaieties and the early work of Rodgers and Hart — when wit, syncopation, and urban irony first fused into a new sound for a new age.

Buy it here

Lorenz Hart: A Poet on Broadway by Frederick Nolan

A richly researched biography that delves into Hart’s mercurial personality, his collaboration with Richard Rodgers, and the lyrical brilliance that defined his career. Nolan traces how Hart’s blend of sophistication, humor, and emotional candor transformed Broadway lyrics into modern poetry — revealing the man behind the sparkle and the melancholy beneath the wit.

Buy it here

The Sound of Their Music by Frederick Nolan

Nolan's book is a companion piece to his biography of Hart. Whilst this book focuses on Rodgers and Hammerstein, there is an engaging dual portrait of Rodgers and Hart that examines their creative chemistry and the tensions that fueled their innovations. Nolan situates the pair within the broader soundscape of the interwar years — a world of jazz, irony, and longing — showing how their songs mirrored the rhythm and restlessness of modern urban life.

Buy it here

“Slaughter on Tenth Avenue ballet sequence - Words and Music (1948)

An example of Hart and Rodgers’ innovation in merging ballet and musical theatre storytelling (though not many Hart lyrics on display here!)